The Girl Nobody Knows

Hollywood's greatest mystery is IRENE DUNNE - who is simply herself

There's an old saying that still waters run deep. And that, perhaps, best describes Irene.

By REGINALD TAVINER

IRENE DUNNE made her first bow on the stage of life exactly at midnight. Perhaps that's why, as far as she is concerned, Hollywood is still much in the dark.

Ordinarly, when a new star flashes across the cinema sky like Irene did in "Cimarron," and then "Back Street," the whole colony knows all about her at least by the next day. But the quiet, enigmatic Miss Dunne has been on the screen for almost three years now, and still Hollywood hasn't been able to figure her out.

On the face of it, there wouldn't seem to be anything so mysterious about such an essentially normal person as Irene. Her biography is simplicity itself, and she appears at first blush to be as typically a homegrown product as sorghum and sarsaparilla.Yet the planets must have had their wires crossed or something, for it was a most complex personality that they ushered into the world at Louisville that night.

What other motion picture star, for instance, would dream of singing over the radio incognito, just to keep in practice? Irene does it often, and so the next time you hear a full mezzo-soprano warbling under a trick name, listen carefully and see if it isn't the same voice you heard in "Back Street." That's just one of Irene's unique ideas.

AS a youngster along the Ohio River, where her father was a steamboat captain and she lived until she was ten years old, Irene was pretty much of a madcap - the exact opposite of what she appears to be now. Then she was a terror to the neighbor boys, her chief delight being to sit on the bank of the old swimming hole so that they couldn't come out until she went home. Incidentally, when she did go home she left their clothes behind her - all tied up in knots. We called it "chawing raw beef," when I was a kid.

Once, when her father was ill and couldn't take his boat on the daily run, she took command and made the trip for him. Whenever she thinks of that episode now it gives her the chills to realize the risks she ran - not on her own account but the boat's - but it still remains the hightlight of her life.

It was on that same river that she first became stagestruck. Fate, she believes, must have had a lot to do with that, for it was on the old floating showboats that she saw her first play. And it was as Magnolia in Ziegfeld's "Showboat" that she scored her first big hit as an actress. Virtually an unknown, she played for seventy consecutive weeks on tour.

How the little girl wandering along the banks of the Ohio River, staring open-mouthed at the tawdry, but to her wonderful glamour of those showboats, herself realized the ambition they instilled in her, is a story in itself. In the beginning it was too much even to dream about, and so she decided to become a school teacher. She got her teacher's diploma and everything, but then fate stepped in.

READING a newspaper one day, she saw that Ziegfeld was looking for a lead in a musical comedy. It was probably only a publicity story, because Ziegfeld had the lead already picked; but Irene didn't know anything about publicity stories then, and so she went blithely to the theatre to try out. Ziegfeld had to stand back of the story and give her a hearing, and so impressed was he that he gave her the part.

As Sabra Cravat in "Cimarron," Irene did exactly the same thing, only this time it was in a dramatic instead of a vocal way. They tested every possibilty in Hollywood for that role, and then Irene got it. What she did with it the world already knows - but you can't tell Irene there isn't any Santa Claus.

From Louisville, where her father had lived for generations, Irene moved to St. Louis, where she was educated at a convent, and from there went to study at the Chicago Academy of Music. It was there that she almost became a school teacher, had not the newspaper clipping intervened. Her parents, although having no objection to the concert stage, nevertheless were opposed to the theatre; so Irene, to get her chance, had virtually to run away from home to New York.

SHE arrived on Broadway with one suitcase and an overwhelming fear, and she says that her first impulse upon seing the "big town" was to run right back again. So scared and so unfamiliar with the city was she that she rode one whole day back on forth on the shuttle subway before daring to get off.

Then a taxi-driver took her to a hotel which, as she knows now, was not exactly the right one for a lady traveling alone. All that she found out later. It was in New York that she met and married her dentist husband, Dr. Francis D. Griffin, and that marriage is just another of the things about Irene Dunne that Hollywood doesn't understand.

Speaking of the present arrangement between her husband and herself, Irene says that it is ideal. He remains in New York to attend to his practice, going to Hollywood once or twice a year, while she makes trips back there between every picture. While she is working, she spends every Wednesday and every Saturday night sitting at home at the telephone, waiting for him to call her up. The call may come at seven in the evening of three the next morning - but it always comes.

"I couldn't advise others to try such a long distance marriage," Miss Dunne told me, "but for us it works perfectly. We are three thousand miles apart, it is true, but the big thing is that we each have our careers without interference from the other. My husband can't leave his practice and I can't leave Hollywood, but neither of us has any thought of giving up either the career or each other. Some day we shall again live in our 'honeymoon' apartment - but in the meantime, for us, this is the best possible way."

The apartment of which she spoke was furnished for their marriage, and is occupied every time Irene goes to New York. While she is in Hollywood, however, the doctor lives with his wife's brother at his club. And Irene lives with her mother in her Beverly Hills home.

IRENE DUNNE is perhaps the one person in Hollywood who does exactly as she likes. She is positive in her desires, and carries them out without regard to anything or anybody.

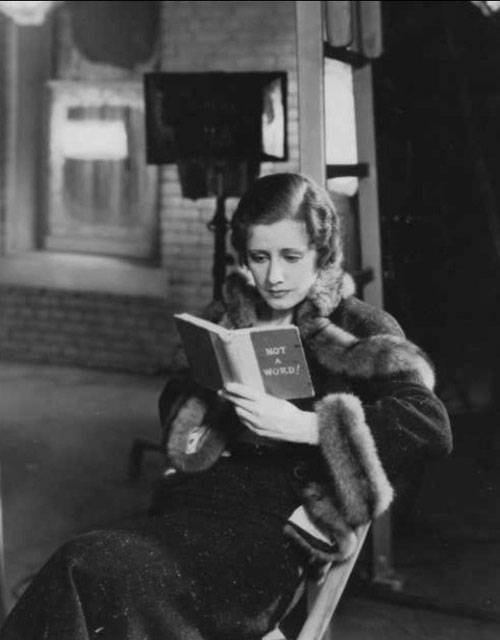

Irene frankly admits, that she does have a terrific "temper," which she has been trying to get under control all her life. This temper, she says, has got her into many a scrape; and in order to curb it she carries a little book which she calls her "mad book."

The name of it is "Not A Word," and when Irene feels herself about to hit the ceiling, she hurriedly retires to a corner and reads furiously. Often, she says, it works beautifully, she psychology being the same as Napoleon's counting ten. But she couldn't been blamed for one outburst she had, and this time the book didn't work either.

While she was working on her last picture, the assistant director one day gave her an early call for the next morning, and then, when that set was cancelled, forgot to tell her. Consequentely, Irene came to the studio and spent two hours on her make-up before she found out that she needn't have come. She says that she not only read her mad book, but counted up to a hundred on that occasion, and when she had done both, found that she was more riled than ever.

No, the assistant director didn't neglect to keep her calls straight after that.

ANOTHER thing that makes Irene inordinately mad, but about which she doesn't seem to be able to do anything, is missing shots at golf. She is proud of being a member of the Hole-in-One Club, sinking her qualifying stroke on the Pebble Beach course at Del Monte; but she's always buying clubs to replace the ones she breaks when things are not so good at Lakeside.

Just now, Irene is in open rebellion. In both "Cimarron" and "Back Street" she portrayed virtually the seven ages of woman, and she declares that she is all through growing old before her time. Beautiful old ladies are beautiful, she says, reminding you of your grandmother and everything, but they're still - old.

"One more silver thread among the gold," she said, "and I'll be tagged just as inevitably as a second-hand automobile. Instead of having a career, I'll get an honorary membership in the old ladies' home."

Unlike many actresses who have forsaken the footlights for the more lucrative fleshpots of the screen, Irene doesn't try to ritz Hollywood with her Broadway superiority. On the contrary, she prefers the screen to the stage, and expects to stay in pictures until she retires permanently.

"Here I play to a vastly greater audience," she declares, "to the world, in fact, instead of a single house. Besides, each role is different, and constant repetition of even a role like 'Showboat' become monotonous to me."

Her dream, eventually, is to live in a little cottage just outside New York and presumably raise babies while her husband pulls teeth.

Irene and different terriers. ca. 1932 - that's probably "Ruffy" - and ca. 1935.

NEITHER has Irene gone Hollywood. As a matter of fact, she has done just the reverse. She lives quietly, with only a couple of servants and a wire-haired terrier named Ruffy, besides her mother. She detests openings, and rarely goes to Hollywood parties. She would much rather jump into her roadster and drive three of four hundred miles to a golf course. She is afraid of airplanes and never travels in them.

She does love the beach, however, and her love for it once cost the studio several thousand dollars in suspended production. She owns no beach cottage, as most of the stars do, and so she took her nap in the sun. This particular time she slept too soundly, and when she woke up she couldn't move. Instead of the studio, she went to a hospital for sunburn.

NOTWITHSTANDING both her love for the movies - she is an ardent picture fan - and her success on the screen, Irene doesn't really like Hollywood. She belongs to no cliques and speaks no Hollywoodese. And, unfashionable hereabouts, she pulls down the shades when she switches on the lights.

Hollywood, though it doesn't pretend to understand her, nevertheless adores her. But the cinema folks can't be sure whether she really means the naive mask she wears, or is merely laughing behind it. As for Irene, she insists that hse isn't sophisticated herself, and says that nobody else in Hollywood is, either.

"I like to work here," she asserts, "but I like to play in the East. I can only stay here so long before I begin to feel stagnated. Then I've got to go away until I resume a normal viewpoint."

Looking at her, you get very much the same sort of a sensation that you get when you look down into a well. On the surface everything is calm, placid, unruffled; but down below there are shadows, with nobody knows just what underneath. But at the bottom of the well there is a spring which cannot be repressed, and you get the feeling, somehow, that Irene is like that. It was just such a spring which burst out into that unforgettable performance in "Cimarron."

Hollywood has found that Irene can draw the line exactly halfway between being an ingenue and high-hat. She insists upon being herself, and that leaves Hollywood gasping. Nobody ever knows just what is going on behind those widely-spaced, grayish-brown eyes of hers, and behind that high, broad forehead; she is mysterious as Cleopatra and at the same time as wholesomely refreshing as one of her own mint juleps. She is entirely different from any one Hollywood has ever known.

Hollywood is used to big stars who shoot this way and that on any or no provocation - to the Dietrichs and Negris and Garbos and Bennetts, et al. But for a girl like Irene Dunne, going quietly along her own serene way, numbering her intimates upon the fingers onf one hand and passing up the giddy, frivolous social life completely, there is no precedent at all. No marquises pay court to her; instead she sits at home, alone, and waits for her telephone calls.

Hollywood gives it up.

There is an old saying that still waters run deep. And that, perhaps, best describes Irene Dunne.

(The New Movie Magazine, October, 1932)

The Irene Dunne Site

The Irene Dunne Site