Revealing The Life Of Irene Dunne

By Adele Whitely Fletcher

... Her stage triumphs... The advent of Dr. Francis D. Griffin - and domesticity ... "Show Boat"... Hollywood successes - and the sweet sorrows of a long distance marriage

THE Dunne family lived in Louisville, Kentucky, when Irene was a little girl. Later they moved to St. Louis, Missouri, and Irene went to a convent school. The family were comfortably off - Joseph Dunne was a successful engineer. A big handsome man - and a wonderful father. He died when Irene was in her 'teens. It nearly broke her heart. But gradually - there was work to be done and y younger brother, Charles, to help forward in life - Irene recovered. She studied music at the Chicago Conservatory. Came to New York to get a job. And after some lean months, got one in Peggy Wood's "Clinging Vine." She understudied Miss Wood - and one night the star couldn't be there. Irene played the role - so well that the producers sent her on the road with the show in summer. Then, there followed a successful summer season in Atlanta, Georgia. A gay season. Lots of parties. And at one of them, Irene met the most attractive man in Atlanta. They saw a lot of each other. Everyone told Irene he'd had heaps of girls and never took any of them seriously. But that was all right with Irene. She had her career, after all. Then - one day - he didn't telephone...

Irene was resentful. She had not planned to take the young man any more seriously than she felt he planned to take her. "Girls as well as boys can have romantic interludes withoug losing their hearts," she had reasoned. "Quite as well." And even while she had said all this to herself she had been falling in love.

Later that morning when her young man did telephone at last she was extremely cool. She wouldn't be like all the Atlanta debutantes who went mooning over him. He'd never know how she felt. On this score she was determined.

Her coolness brought him, post-haste, to her hotel.

"I had to come," he said. "You sounded so strange. What is the trouble?"

"Nothing," Irene told him with elaborate indifference. "Not a thing. Why you think anything the trouble is more than I can see."

But her eyes weren't indifferent. They weren't any more indifferent than his eyes. And in his eyes his heart hung.

Now their casual days were over. They were in love. They both knew it. the both counted only those hours which they spent together.

Her Atlanta engagement ended, Irene had to return to New York. He followed. Without her quiet loveliness he found his home city as barren as a prairie. In spite of all the intrigued debutantes. In spite of all the designing mammas.

In New York, with Irene between engagements, they were together form early morning until late night. They were going to be married. Then, suddenly, they weren't going to be married at all. The crush, young and violent while it lasted, began to wane. Irene started rehearsing for "The Prince Chap." The young blood turned back home.

Rehearsals for "The Prince Chap" were held on the New Amsterdam Roof. One morning Irene recognized Florenz Ziegfeld going up with her in the elevator. She was glad she was wearing a smart blue crepe, that her small hat with its perky nosegay of garden flowers was ultra smart. Aware of Ziegfeld's eyes on her she turned her best angle toward the famous girl-glorifier.

"Ziegfeld Offices," called the operator, bringing the car to stop, flinging open the grille door.

Ziegfeld stepped aside for Irent to pass. He assumed any pretty girl in that elevator must be getting off at his floor. When Irene made no move to pass he looked surprised. Surprised and a little put out, too.

Ten minutes later a business-like young woman came up to the roof. Irene was sure she was Mr. Ziegfeld's secretary and that she was there to see her. She was.

"Did you just come up in the elevator with Mr. Ziegfeld?" she asked, coming over to Irene, marking the perky nosegay of garden flowers on her hat by which, it developed, she had been told she might recognize the right girl.

Irene nodded.

"He'd like to see you," she secretary said. "He's casting."

"Thank him," Irene said, "and explain I'm in rehearsal here."

"Nevertheless," she says, "I had a strong feeling that one day I'd be associated with Florenz Ziegfeld. But I did not dream of the great change that would come into my life in the meantime."

And little did Irene dream the evening friends telephoned to ask her to a party and she hesitated whether to go or remain home and study, dead set upon becoming as proficient in her French as a Parisienne, that the future pattern of her entire life rested with her decision.

It was the new red dress hanging in her closet which decided her.

"I'll go," she said.

SINCE her last crush had petered out she had been studying and working steadily. She was ready for gaiety again. As a matter of fact, this was probably what had prompted her to buy that dress the week previous.

It was a very simple dress. Very smart. Owning it made dressing rather exciting. Irene brushed her soft hair until it lay smooth and bright. Her quiet eyes were eager.

Later, in the famous Gold Ballroom, the dance music was perfect. It had swing and rhythm. Even going from one partner to another, even walking out to the dance floor, Irene must dance a little. And hum a snatch of whatever song they happened to be playing.

It was after a waltz when she was leaving the floor with her partner that she saw a tall, well-built young man, very dignified in his well-cut tail coat, coming towards them.

It was all very casual. There was nothing about it to warn her that in this moment lay her destiny.

"Irene," said her partner, "may I present Doctor Griffin?

"Doctor Griffin, Miss Dunne."

Irene smiled.

The doctor bowed.

Never, Irene decided, had she seen more level blue eyes. He was serious-minded, this young doctor. Of that there could be no doubt. But he had humor, too. His leve eyes were washed by laughter.

"Could I have the next dance?" he asked, "or isn't that possible?"

"I'm sorry, " Irene said. She was sorry. She liked this tall fair New Englander. Tremendously. Immediately.

"What dance may I have?" he asked. He would pin her down.

"The third after this?" She quite intended it to be a question but her voice leaped out of control to make it a very eager, hopeful question. The tone of her voice said, quite plainly, oh dear, I hope that will be all right!

"Thank you," he said, "I'll come for you." He had a nice dignity. And a friendly warmth - a very sincere warmth - besides.

Too many times when you really talk to a man he becomes less attractive than he promise to be.

However this was not the case with Francis D. Griffin of the New York Dental Association. After the first dance Irene liked him better than ever.

He asked for her telephone number and she gave it to him.

In the car on the way home Irene's friends teased her.

But Irene smiled and refused to commit herself. Francis Griffin might never call after all. Indeed he didn't call her for three weeks. Then one morning Rosemary Paff, with whom Irene was rooming again, knocked on her door.

"Telephone, Irene. A Doctor Griffin."

He wanted Irene to have dinner with him that night. He suggested he come for her fairly early and they drive up the Hudson. It was March but there was spring in the air.

He drove a low blue car. And he drove it well. You had no fear he was going to bash into the car ahead, that he wasn't going to brake it neatly when he rounded curves.

They arrived in time to watch the sun spill its fire on the swift Hudson before it dropped behind the Hills on the Jersey shore. Then they went inside to the table he had reserved.

"Did it matter to you when I didn't call you?" he asked Irene.

"Yes," she answered honestly. "I was surprised you asked for my telephone number if you didn't mean to use it."

"I didn't telephone," he told her then, "because I knew you were the girl for me and I didn't feel I was quite ready ... So ... I stayed away. As long as I could."

"I liked him, too," Irene told me. "Ever so much. More than ever after that drive and dinner. Like many New Englanders - he was a neighbor of Calvin Coolidge's in Northampton - he finds life a serious business. But he's never - well - heavy about it."

TOGETHER Irene and Francis Griffin rediscovered New York City. They found the streets from the end of which you could best view the sunset. Late afternoons he was through at his offices and Irene was through rehearsals and study for the day.

Her next engagement would be in St. Louis. With a summer repertoire company similar to that in which she had played in Atlanta the summer previous.

The St. Louis engagement would take her away from him. That wouldn't be desirable, goodness knows, except that away from him she might be able to think more clearly. At his side she wanted only what he wanted, even if she had wanted something diametrically opposed to this a few minutes previously.

"It's better for both, of us that I go away for a bit," she told him that night they dined together before he took her to the train. They both had been strangely silent all evening. "It will give us time to think, time to make quite sure."

"I need no more time," he said quietly.

It was very hard to walk through the train gate, to leave him. But if she didn't turn around, if she kept right on, one trimly shod gray foot in front of the other, her eyes on the porter's scarlet cap, she soon would be on the train. And since she had not gone through the gate until the very last minute the train would start almost immediately. Then there would be nothing she could do about it. She would be on her way.

"By July first," laughs Irene, "I was back in New York. Shopping for my trousseau. While my mother planned the details of our wedding at aun uptown church and the reception which followed at the Plaza.

"We were married on July sixteenth. Not being superstitious I wore green. Green chiffon. And a large hat with a crushed apple green velvet bow."

Only a few Dunnes and Griffins heard Irene make her vows in her steady, soft voice, heard Doctor Griffin make his vows quietly but obviously gladly. It was later at the Plaza reception that all their friends gathered round to whisper they never had seen a lovelier bride, to nibble on little cakes rich with marzipan, and brush away the silly tears people always shed at weddings. One of Irene's school friends caught her orchids, silvery white like an angel's wings.

They sailed, Irene and Doctor Griffin, on the Berengaria. While the busy, puffing tugs nosed the great ship out into midstream they stood together on the top deck. They were off. To another world. And they stood hand in hand.

In Paris the lived near the Bois and one sentimental afternoon they laid roses on the tomb of the Unknown Soldier, roses red as the blood he had spilled for his country. For the home they would make together they bought - in a little shop on the Rue St. Antoine - dessert plates which had belonged to an unhappy queen.

In Switzerland the blue of Lake Lucerne spread below their high dormer windows. Here they bought fine linens and embroideries. For a song.

In England they lived, very grand indeed, at the Carlton. They dined with friends in Mayfair. They rode in Hyde Park. They found old Sheffield candelabra to light their dinner table through the years that were to come.

Then they came home. To adjust to everyday life and find it anything but prosaic, quite as glamorous in its own way as their honeymoon had been. After Doctor Griffin had left for his office Irene would do her ordering, give instructions for the day that her household might run smoothly. Then she would go to her piano. She would continue to study. That had been agreed upon.

Curiously enough, considering how ambitious and busy Irene previously had been she was content. From time to time offers came to her from producers casting new productions. She had no interest in them.

Then one night she, Doctor Griffin and a party of friends went to see the new Ziegfeld production of "Show Boat." Irene sat through it in a trance. The music bewitched her. It was as if all her life she had been waiting, studying, serving an apprenticeship, that one day she might play a role like Magnolia.

A week or two later, unbelievably enough, the was offered the role of Magnolia in the road company of "Show Boat."

"And that offer really frightened me," Irene said, "Because I couldn't bring myself to give it up."

She went to Doctor Griffin that night when he came home.

"I want you to be happy above all things," he said affectionately. "You've turned down everything else that has been offered you, apparently without a qualm. So now, seeing how strongly you feel about this, I wonder if I have the right to influence you, one way or the other."

"Show Boat" opened in Chicago and, for part of the time, Mrs. Francis D. Griffin became Irene Dunne again.

"And now," Irene told me, "my husband is as enthusiastic about the things I do, over any success I have, as I am. More so, sometimes.

"It isn't pleasant being seperated as often as we are. Neither of us pretends it is. But we are together as much as possible."

FROM Chicago the "Show Boat" company went to Boston. There they closed for the season. On next to the last night Ziegfeld was in the audience. In the second row on the aisle, he sat. To watch all of them and choose those he wanted for the company when it openend again the following September.

There was a tremendous excitement backstage. Some gave better performances than usual that night. Others, too nervous, gave performances below their standard. Irene Dunne never played a more colorful, glamarous, romantic Magnolia in her life.

At the end of the last act, taking her bow, she caught Ziegfeld's eye. He nodded. That was all. But later a note came back, making it final. By all means he wanted her for Magnolia the following autumn.

"And," he added graciously, "I also must thank you for one of the happiest evenings I've ever spent in the theater."

This note, needles to state, if one of Irene's most precious possessions.

After a summer on the golf links and at the shore Irene was more than ready to work again.

"It was," she told me, "while I was playing Magnolia in Baltimore that Hollywood became interested in musical pictures. There were always rumors that scouts from the studios were in the audience. But I never paid much attention to this until the night William LeBaron of RKO came backstage. He had, it appears, had reports on me and had come to see me for himself."

A month later Irene was under contract to RKO. Doctor Griffin had said he could manage for a little while.

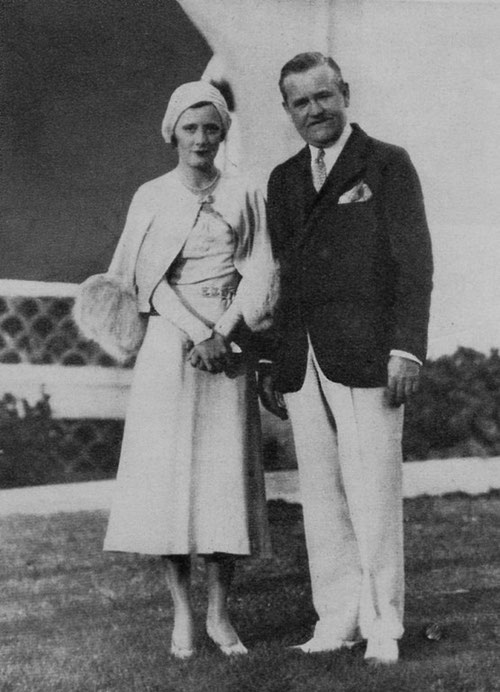

Adelaide Dunne who had come our west with Irene, posed with her for the Hollywood reporters.

And Irene wished the serious husband she had left behind in New York might be there too. There was nothing that would not be better with him at her side.

It was several days before she was asked to report at the studios. Had she started to work at once she might not have gotten so miserably home-sick.

During the day, before her mother, she fought back her tears. And exerted herself to seem happy and interested. Even enthusiastic. But there was not pride to forbid her crying herself to sleep. Morning after morning she awoke with wet lashes, exhausted.

When Doctor Griffin didn't telephone she was wretched. When he did call, after he had hung up, it was almost worse. Irene wondered whatever had possessed her to leave him, even to consider motion pictures.

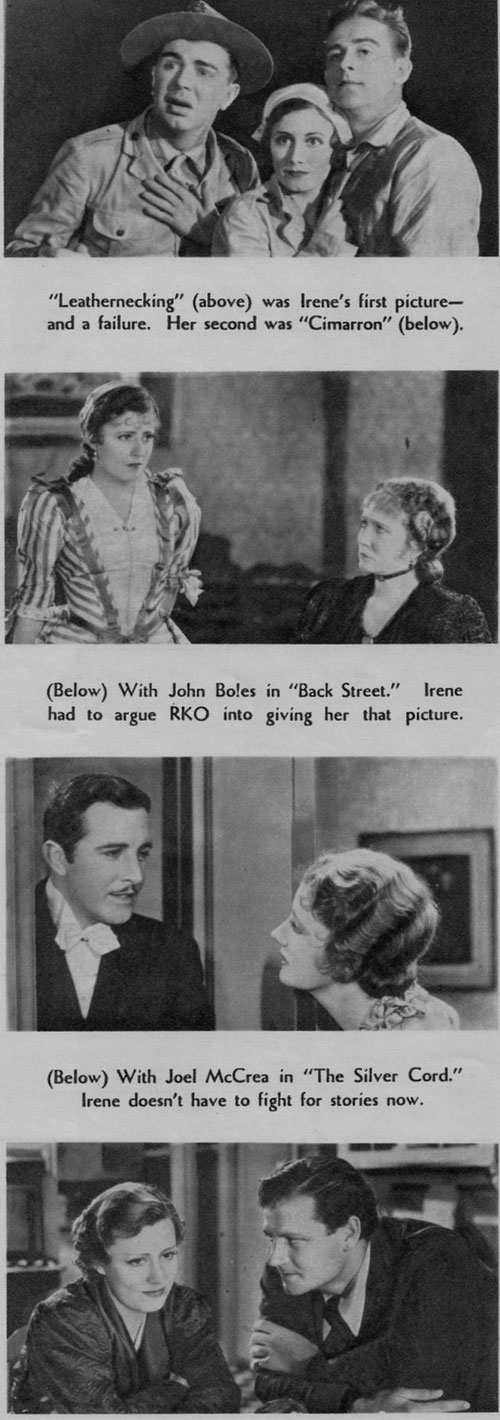

But there she was and by this time her first picture, "Leatherneckers,"[sic] a musical version of "Present Arms," in which she played with Benny Rubin, Louise Fazenda, Lilyan Tashman, Eddie Foy, Jr., and Ken Murray, was under way. When it was over she planned to ask for her release and travel east as fast as the first train would carry her.

However as things developed she did nothing of the kind. "Leatherneckers" turned out to be a very bad picture. And at the same moment the vogue for musical productions, the market having been flooded with too many bad ones, ended.

"What are we going to do with Dunne?" the RKO officials asked one another. "We brought her out to do musicals and we're not making any more of them. But she's under contract."

Under such circumstances Irene couldn't leave. She might have renounced a successful career to go home to her husband but she couldn't return a failure. She is softly spoken and quiet eyed but she has surprising strength, unlimited courage and undying determination.

Another thing. They were testing girls for the role of Sabra Cravat in "Cimarron." And here was a role Irene wanted to play in the very worst way.

The studio executives were horrified the day she asked for this plum part. She quite upset the conference at which, politely and with considerable beating about the bush, they were trying to decide what was to be done with her.

"You've tested practically everyone else in Hollywood for the part of Sabra," she told them. "You've spent a fortune testing people. Why not, at least, give me the same chance your're giving utter strangers, utter outsiders?"

The test, they informed her gravely, would be a difficult one. She must play the three ages. Sabra as a young girl, as a woman, and as a grandmother. But, magnanimously, since their gravity didn't appear to terrify her in the slightest, they agreed to let her try.

She went home jubilant.

"I'm going to play Sabra," she cried, running to Doctor Griffin who was out for a visit. "I'm going to play Sabra."

Then little by little, he got the whole, right story from her. That was Saturday. She was to take her test on the following Monday.

HE saw how intensely she felt about this, how desperately she wante the role. And he wished from the bottom of his devoted heart there was something he could do that would help her towards it.

All day Sunday, Irene worked on the dialogue and the business.

"You go play golf," she implored him. "You love it so. After all, my dear, this is your holiday. You must not spend a day indoors, cooped up with a ranting wife."

But Doctor Griffin only smiled and shook his head. There might be something he could do to help and he was determined to stay and do it. They closed themselves into their room. He sat on the bed, her audience, while she tried a line of a bit of business first this way, then that.

"And," laughs Irene affectionately, "for a man who hadn't wanted his wife to go on with her career, he cooperated with more enthusiasm and intensity and sympathy than you might believe possible."

The next morning Irene was at the studios early. The wardrobe mistress brought her the three sets of clothes that had been made for the Sabra Cravat tests and, over the week-end, altered to fit her.

Irene looke the clothes over carefully. Those planned for Sabra grown older didn't please her at all. They weren't clothes she felt Sabra would wear. The hat especially seemed all wrong.

"Do something for me," she told the wardrove mistress. "There's a woman who works in the sewing-room upstairs, a woman about sixty, well built. She wears just such a hat as I think Sabra would wear. Ask her if I may borrow it for this morning. Tell her I will be very careful of it.

They brought the hat. The woman had been delighte to lend it.

Irene took it from them with a happy little cry. She was like a little girl receiving the very doll she had admired in a shop window. She knew just how she wanted that hat to sit on top of her head.

A fortnight later Doctor Griffin left for New York with a vicarious sense of accomplishment. Irene was going to play Sabr all right. And he felt that sitting on the bed that Sunday, serving as her audience, making suggestions, he had helped her get it. Irene herself was certain he had.

They worked on "Cimarron" for sixteen weeks.

"And," says Irene, "through all those weeks Richard Dix showed me an understanding and cooperation for which I always shall be grateful."

In their trans-continental telephone conversations between midnight and dawning when, for the same toll, they could talk twice as long, Irene and Doctor Griffin planned how she would come to New York when the picture was completed, be there for the premiere. He would give a party for her.

But those happy plans never materialized. When "Cimarron" was completed the RKO officials, aware they had a new brilliant star on their roster, knew well enough what to do with Irene Dunne. Things were very different now. They rushed her into other productions, into "Consolation Marriage" and "The Symphony of Six Million."

After the New York opening, excusing himself from his friends, Doctor Griffin went into a room alone and called Irene across three thousand miles. His voice this night was so deep she could scarcely hear him. That was how she knew how proud he was.

Irene also had to fight for a chance to play in "Back Street." The company executives didn't think she was the type to play the leading character in this story. So again she took a screen test and proved to them, conclusively and for all time, that she wasn't a type put an actress.

Then something happened which made her wonder hos she ever had concerned herself over any of the compartively insignificant worries that had beset her during the last several years. She was preparing to go over to the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios to star for them in "The Secret of Madame Blanche." The next day she was to sit in conference with Adrian about her costumes. She went to bed early. So she would be rested and have a clear mind. Early the following morning her telephone rang.

She wasn't alarmed. She had no idea of the hour. She thought it must be her husband calling. But it wasn't Doctor Griffin on the wire. It was her brother Charles, who was in New York at this time. Doctor Griffin was in the hospital with a burst appendix. They couldn't say exactly how serious it might be. They were operating.

Up and down, up and down the room Irene walked for what seemed to her an eternity. No member of her household could help her. Her husband was over three thousand miles away, in pain, and in danger.

Several hours later, at eight o'clock, she put through a call to the hospital.

"Is he in great pain?" she asked his nurse.

"Well, of course, Mrs. Griffin, you understand in a case like this..." came the noncommital, evasive answer.

"Tell him I've called," she said. "Tell him I'm coming - right away."

At the airport they reported flying conditions were not good.

That night when "The Chief" pulled out of Los Angeles Irene Dunne sat huddled in a drawing-room facing three frightful days and nights.

At Grand Central, Charles Dunne met her. He took her luggage to her hotel that she might go directly to the hospital. In spite of the early hour they permitted her to go to Doctor Griffin immediately.

No one had told him she was coming. He was surprised. When he saw her standing in the doorway he looked unbelieving for a minute and then his serious face broke into a smile.

"He was glad I'd come," Irene explained, "yet upset because I'd had that frightful trip.

"However it was worth that trip just to be there to see for myself that he was out of danger. I had been afraid to believe the last few wires, afraid they were sparing me while I was on the train and there was nothing I could do."

SHE waited at the hospital all day. She sat there beside him even while he dozed. Then at nine o'clock, when hospital lights went out, she went to her hotel.

Next morning she ordered the morning papers sent up with her breakfast tray. To her utter amazement her own face looked ap at her from the front page of a tabloid. "On Town," the picture's title read. Then, underneath, "It is expected Irene Dunne is here to ask for a divorce."

She jumped from her bed, leaving, her breakfast untouched. She must be the one to take Francis Griffin those pages. She hoped he would not credit one word they said. She believed the understanding, the bond between them was too great for him to give such malicious rumors any consideration.

When she reached the hospital there were newspaper men in the corridor. A photographer tried to catch her when she went in.

She went straignt to her husband's room. She had come to comfort him against the wretched, inexcusable injustice of this laughable attack. But in the end he comforted her. He laughed at the ridiculous story that was in the papers.

"Now I'm sure you're a movie star," he told her, a twinkle in his eyes.

Five days later she had to leave him. "The Secret of Madame Blanche" was about to go into production. Adrian had made all her clothes on a model which he had had built to her exact measure.

Doctor Griffin was well on the mend. She was sure of that. When he was able to be up and around there was his work waiting for him. Together they would climb, he in his chosen field, she in her's. There would be interludes in between when they would manage to be together. There would be holidays when he would come to California and they would sail off to Honolulu or stay at home and golf. There would be little stolen trips to New York between productions.

And so it goes ... Since "Madame Blanche," Irene has made "The Silver Cord." Her next will be "Lady Sal." And there will probably be many more.

Unless all signs fail they'll live happily forever after. It isn't so much the number of hours married people spend together when all is said and done. It is rather how close they are during their hours together. Besides, away from the studios, away from work, Irene is first and last Mrs. Francis D. Griffin. And that's the way it must be. That's the way it's been ever since the world began.

And the Dunne girl knows it.

(Modern Screen, September 1933)

The Irene Dunne Site

The Irene Dunne Site